Cataloguing

A vital part of our cultural heritage work is to catalogue our collections. At its core, cataloguing aims to make information available, and as a cataloguer, you build the database that makes up the library catalogue. A large part of this work consists of entering metadata into the system, to make the material searchable. The information reinterpreted as metadata also needs to be read from the books themselves. The cataloguer is the human link between a book and the database where the information about the book can be found.

What does cataloguing mean?

For each item, the cataloguer makes a bibliographic post in the database, with metadata describing the item according to a long list of standards and rule systems which are now frequently subject to change. Here, all data that is specific for the individual item is stated - the older the material, the more information present and taken into account: author, title, edition, place of publication, year of publication, number of pages, illustrations, format and more. At the same time, the subject covered by the book is described using various subject terms and a classification code, both to make the item searchable and to determine its place on an appropriate shelf in the library. Many other details may be added here; whether the book is part of a series, its target audience, any links that may be relevant for the material etc.

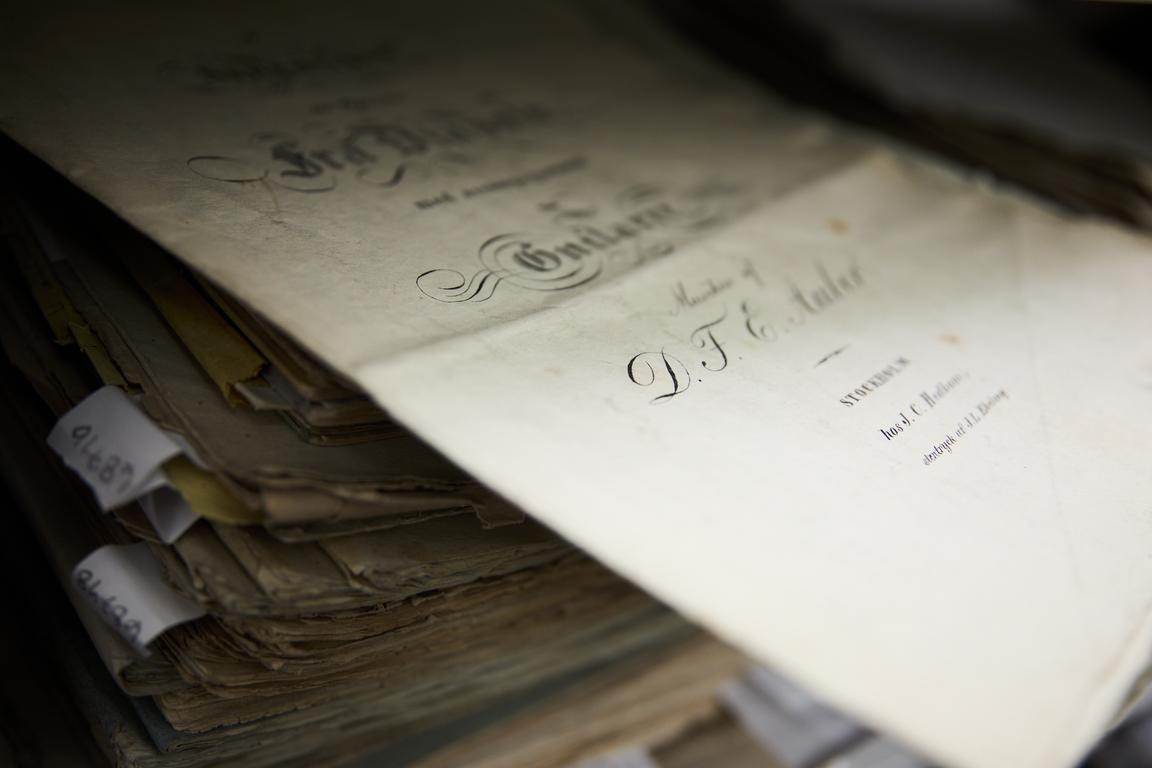

This work requires particular skills, especially when cataloguing older prints: being able to read black letter or German script, being familiar with various languages in order to understand what a work is about, to be able to furnish it with index terms, to establish the correct forms for names of both people and places of publication, to be familiar with hand press era methods of printing in order to determine the format of a book, and so on. Thorough knowledge of history (not least the history of Gothenburg, as well as locally relevant biographical information) enables the cataloguers of the University Library to understand the place of a work in its historical context, as well as its provenance, meaning the history of its ownership, in a way that can be clearly conveyed to the library's patrons.

The work requires a great deal of precision and attention to a host of details. If the cataloguer misinterprets the information or enters it into the system in the wrong way, the retrieval will be compromised in turn. A database is never better than its metadata. If the information contains errors or is missing entirely (which is frequently the case when posts are imported from catalogues established according to different standards), the searchability and search results will reflect these shortcomings.

When working with printed materials, the term for the work is usually cataloguing. Work pertaining to archival materials is known as registration, recording and archival inventory.

Our job is to transcribe and interpret, to enable everyone to browse the material.

Text

Kristina Sevo and Anna Lindemark.

The cataloguing ecosystem

In Sweden, the National Library serves as manager of the national LIBRIS collaboration project. Some 500 libraries are participating in the ongoing project, which provides information about the holdings of many Swedish libraries. LIBRIS is their joint catalogue, updated daily. The participant libraries all contribute to the contents of the database. At present, it includes about 7 million titles in the form of bibliographic posts. All the associated libraries can make use of these posts, by stating that one or more copies of a given title is available in their own holdings. This requires a description of the book (a bibliographic post) made by a cataloguing library.

In addition, each library has its own local catalogue, which predominantly consists of the posts describing the holdings of that particular library. The local catalogue is created by retrieving bibliographic information from LIBRIS.

”But isn't this available online?”

Large portions of a library's holdings may be absent from LIBRIS, or from any digital catalogues whatsoever. This applies mainly to materials acquired long before the library catalogues became digital, which still await retroactive cataloguing. Many of the collections of the Gothenburg University Library are significantly older than the digital catalogues, and the manner in which various items have been catalogued has varied widely.

A kind of older catalogue perhaps familiar to many is the card catalogue. The main card catalogue of the Humanities Library is the Catalog -57. Here, each book is described on an index card, kept in a filing cabinet. Sets of filing cabinets usually come in two versions, one alphabetical and one systematic, arranged by subject. Card catalogues can be scanned and made available online, even if they cannot be integrated in the library's general online catalogue. If the index cards have been made with a typewriter, they can potentially be scanned for OCR (Optical character recognition), to enable free text searching in a card catalogue. How the information is presented on the cards, and what its placement on the paper surface reveals in terms of metadata, is for the cataloguer to determine. Some index cards are written by hand, which further clouds attempts at machine reading. The Catalog -57 of the University Library is an example of a very extensive catalogue, whose contents - in their entirety - have yet to be fully entered into LIBRIS. Meanwhile, a large part of the library's holdings can only be found via Catalog -57, which has been scanned. For anyone browsing for older materials, this is vital information.

Some collections lack even a card catalogue, but may be described in printed or more or less legibly handwritten inventories, sometimes in the form of alphabetically or chronologically sorted lists. Such catalogues can be scanned and made digitally available, usually in PDF form.

Other collections lack catalogues altogether, and sometimes there is nothing but a cursory note about their contents. It takes extensive detective work to gain an overview of what a collection really includes, and from time to time, the work offers surprises at closer inspection, as the cataloguing work provides an entirely new idea of what is really at hand.

Cataloguers work continuously to expand and improve the library catalogue, and ensure that it mirrors the library holdings. At present, it is still necessary to navigate a great number of catalogues, some of which are available online in different formats, in order to get an idea of what books and other materials are actually available in our collections.

How long does it take?

Anyone in charge of planning for an enterprise, and in need of mapping different processes, usually needs details on how long various tasks will take. But how much time is required to catalogue a book? Frustratingly enough, the answer varies widely depending on the book; it might take five minutes, three hours, or sometimes an entire working day. The detailed nature of the work, the demand for problem solving and the importance of correct metadata makes cataloguing a very slow sport. Quick solutions do not always yield the desired results, and may require a lot of cleanup afterwards, which takes even longer.

Worth noting is that anyone looking to make digitised or digitalised books searchable and available, needs the original book to be catalogued first. A behind-the-scenes challenge for a great many digitalisation projects!

Cataloguing challenges

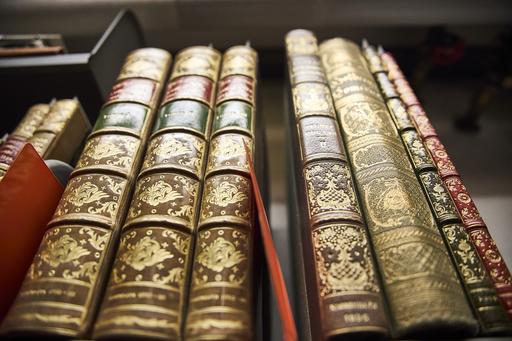

Old prints

Old prints are frequently requested for digitalisation. The term covers books and brochures printed during the hand press era. Roughly, this includes materials printed in Europe between 1450 and 1830. In China, books were printed already in the 5th century, and with moveable type from the 11th century onward.

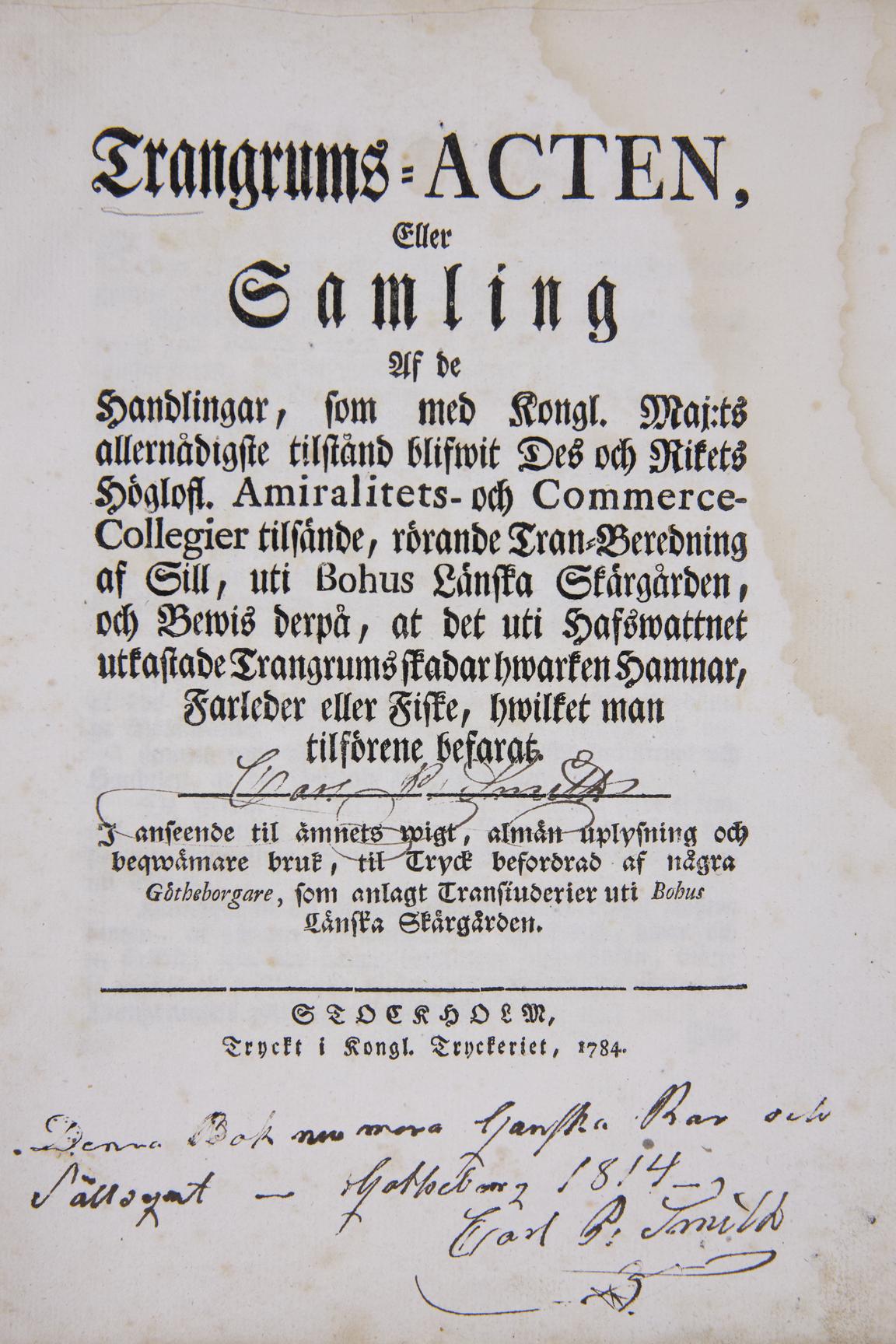

When cataloguing old prints, all details appearing in a work are essentially rendered exactly as printed - hyphens, any misprints if present, and compound nouns written apart in obsolete fashion - a very common feature of older Swedish texts. This in order to easily distinguish between different printings, simply by scrutinizing the text on the title page.

Print styles

Fraktur or Gothic style was long the standard print style in the Germanic parts of Europe until the 18th century, when it was gradually replaced by Antiqua or Roman type. Nations dominated by Romance languages used both styles for many years.

Languages

Being able to understand and interpret various languages is a must for anyone cataloguing special collections - preferably dead languages, at that. Older Swedish can be a challenge in itself. It isn't necessary to be fluent in the given language, but you need a basic understanding of its grammar and syntax, as well as common expressions and phrases for the context. Older materials are often interdisciplinary in nature. The same book may touch upon medicine, literature, astronomy and magic. Scholars will be scholars, indeed! Regardless of the contents, you need to grasp what a book is about in order to provide index terms and a classification code for it.

The majority of the old prints in the university library collections are written in Latin. For centuries, Latin was the lingua franca of the western world. Beyond Latin, German, French, Ancient Greek and Dutch are frequently represented. In earlier years, English was not commonly used in our part of the world, and regarding Swedish, very few scientific books were written in Swedish before the 18th century - however, there are many broadsheets and a host of religious literature written in Swedish and published in the 1700s.

Transliteration

Sometimes, understanding what it says on the page is not enough. You also need to be able to transliterate Ancient Greek and other languages to Latin characters, to ensure the material can be found in the library catalogue. Transliteration means rewriting one set of characters into another. One character may correspond to several in another, known alphabet.

Transliteration is made according to a given standard. When it comes to Greek, there is a difference in transliteration depending on the age of the material: books printed from about 1450 onward are treated according to the transliteration rules for modern Greek.

Regarding Russian written with the Cyrillic alphabet, the Swedish public libraries and university libraries have so far been unable to agree on a single standard, and are currently still using different transliteration standards. This naturally causes a number of problems when browsing catalogues. How to spell in order to find the right results? Other nations in turn have their own standards, which creates new challenges when importing posts from foreign library catalogues.

Name forms – personal names and place names

Name forms, meaning different spellings and renditions of the names of people and places, is a complex and intriguing field. Most modern languages have undergone one or more spelling reforms, and before these, most things might be spelled quite liberally and in varying ways. Regarding people's names, this held true even after the spelling reforms. The practice of latinising names, too, was more of a rule than an exception for as long as Latin remained the standard international language of science.

Theognidos is called precisely that in Greek. In Latin, however, the name is rendered in the genitive case, Theognidis and in the Swedish Nationalencyklopedin he is listed as Theognis – a Greek poet from about the 6th century BCE.

The cataloguing rules of LIBRIS state that we should use the name form corresponding to the language of the country of origin of the person in question. What this means, exactly, is often subject to various interpretations. However, the Nationalencyklopedin takes priority over any given cataloguing rules.

One example is the publication place called Ultrajecti, which translates to ”thrown furthest from civilisation" and is a latinised form of the Dutch Utrecht, currently in a marginally more central location. Places of printing or publication as stated in older materials generally have latinised names: Lugdunum Batavorum (Leiden, Holland), just Lugdunum (Lyon, France), Agrippina (Cologne), Lutecia (Paris) and the Swedish Lincopia (Linköping), Holmiae (Stockholm), Gevalia (Gävle), Junecopia (Jönköping) and Wexionia (Växjö), and that's not even starting on the fictional places such as Canabacum or Tripoli (not the Libyan city) featuring as places of publication of works containing political or religious criticism, where involvement in the manufacture of the books might pose a risk.

Marginalia

People have always made notes in the books they own. The most common things we find are signatures or names, which might provide valuable information on the provenance of a book, but sometimes there are more extensive comments in the margins, or little messages.

To the cataloguer, the rule of thumb is that a handwritten note in a book must be legible in order to make its way into a catalogue post. Ownership and other details pertaining to an individual book is presented in the associated holding post of the specific library, as such information concerns a particular copy only. This kind of information may be highly valuable to researchers. Sometimes, handwritten notes in a book may be virtually illegible, and in that case, a note about that can be made in the post instead.

Formats

For old prints, the stated format of a book reveals how many times the manufacturer has folded the sheets of paper that make up the body of the book. Primo is the term for the sheet taken out of the papermaking frame. The process creates chain and wire lines in the paper, which are useful when assessing the format in front of you.

Folio, which also means to fold, means the sheet has been folded once. Quarto means two folds resulting in four sheets. Octavo is three folds – eight pages. Duodecimo is four folds, meaning sixteen smaller sheets made from the original one. The format becomes incrementally smaller. In addition, there are several full- and half formats, and many variations.

When stating the format of a book, you start by counting the number of pages in a signature or gathering, meaning folded sheets that are bound (sewn) together, and thereby easily discernible. The signatures are distinguished by signature marks, often in the form of the letters of the alphabet. Sometimes, there are no signature marks, in which case the lines of the paper or the size of the book might provide useful clues. The composition of signatures is key to the identification of different copies and printings.

Pagination

Pagination can be incredibly straightforward - if you are lucky, the first page is number 1 and the last is, say, 250, and at this you can simply state that the book has 250 pages, provided the signatures occur in sequence. But pagination might be uneven, partially or entirely missing, or include errors. There might be gaps in the pagination, too, and this must all be stated when cataloguing. From time to time, you might come across a book that has individual pagination for each signature. Plates, inserted leaves and folding leaves frequently diverge from the general pagination of a book.

Provenances

Beyond written notes on how the book has been acquired, owned and donated, you might come across one or more bookplates. These details are all stated in the holding post for the individual copy of a book.